The King Herself

The King Herself

2 April — 31 May, 2022

T-Michael/Norwegian Rain Oslo NO

Photo: Thando Sikawuti

2 April — 31 May, 2022 Norwegian Rain/T-Michael Oslo

On Nicole Rafiki’s solo show „The King Herself“

My fascination and appreciation of Nicole’s work stems from her fearless stance on anything she feels passionate about. This attribute is lacking in the zeitgeist we are in. We are easily dissuaded or persuaded, and the resulting effect strengthens the already prevalent numbness in our society.

Socio-political art is essential to our unlearning of the ongoing detrimental effects of all that we’ve learned over the past 300 years. One could debate or argue over the effect of the aforementioned indoctrination or one could effect a change, from one’s own front porch. I want you all to go in and indulge in Nicole’s work firstly as a beautiful interpretation of her sensory perceptions. Just that.

On your way home to the safeness of your abode, do ponder on the numbness in our society.

Or not. Either way, I will still be fascinated by Nicole’s art and intellect.

Peruse well.

T- Michael, curator

—-------

The work of Nicole Rafiki reaches across time. It walks through loss and traverses the globe. Her artistic techniques – if ‚technique‘ is even the right word to describe her practise-based intuitive methodology – encompasses photography and/as storytelling, careful forms of textile contact, and deep research into cultural symbolisms and forms of ritual, a research, which in turn becomes ritual as history writing. The histories Nicole Rafiki invokes in her artworks are of both geo-political dimension and personal depth.

The seven images that are at the center of Rafiki’s exhibition „The King Herself“ take as their starting point one of the most intimate experiences of time: finitude as it is experienced in the loss of a loved one, through the loss of family. Each of the photographic works on show is a different step in a process of mourning Rafiki underwent after the recent loss of both of her grandmothers. After having been based in Norway for many years, Rafiki had just started out on a path of return to her grandmothers in Kongo in order to study particular artistic symbols and practices passed down in Luba culture where part of her spiritual and cultural heritage reside. The sudden loss of both of them right before this moment of reconnection left the artist with a sense of being severed from her roots.

The works on show are a response to this to uprooting, a form of auto-portrait as much as they are a kind of auto-healing. Reading the images as panels from left to right – which is only one possible direction of approaching them – conveys different stages of grief that run through the artist’s body. In the first image on the left, the artist is lying on the floor on embroidered cloth. A rug perhaps, mirroring the sensation of having the carpet pulled away from under your feet in the face of the death of another. Here in the image however, the cloth grounds the artist, carrying her as she pauses to rest from the manifold loss that has occurred.

About to share in the experience and memories of her grandmothers, Rafiki’s immediate connection to them may have been cut off abruptly. Her artworks however, speak to the ways in which she has managed to transform this state of being severed into a channeling of connections that reach even further back through time to other ancestors past.

The process that leads to Rafiki’s photographs is less the staging for a particular scene, but crafting the photographic elements becomes part of the work, a kind of durational performance to which the resulting photographic works only form one element of many. In said first image, her hand holds a Lukasa, a Luba memory board used for recounting historical events during spiritual rituals or political deliberations. Rafiki may not have been trained formally in how to trace the different beads on the board with her fingers in order to use it as a mnemonic device for narration, but the tracing of connections she practices in her work are themselves based on a kind of oral history, a transfer of knowledge that reaches for intergenerational contact and follows a different epistemology, one that is not primarily invested in visual ‚proof’ or first hand ‚evidence’. What can learning – a being taught even if one is not being taught through things handed down directly – look like?

Rafiki has conjured different colors and memorial objects, both old and new, to forge her own space of connection with those who walked before her, ranging from a bright red portable music box that provides solace, to Converse shoes that reach across time to the 1930s, and connect back to yet another continent, where the sneaker company became one of the first companies to sponsor an all-Black basketball team, the New York Renaissance, or „Rens“.

Walking in someone else’s shoes takes on a deeper meaning when you need to go on without those who came before you. Is there a way for empathy to travel from the past to the future rather than only being directed toward those we see when looking back? The images in „The King Herself“, for one, circle back through time. They can be read in reverse, or in no particular order at all.

Mourning, after all, is not a teleological journey at the end of which the goal is to leave something, or someone, behind. It requires an understanding of circular time, and of circular experience. As Rafiki emerges as a self-taught practitioner of Luba practices of healing, mourning has become a kind of time travel. From here, the images take off in the direction of a wider picture, panning toward the question of how knowledge is passed on through time on a geopolitical level.

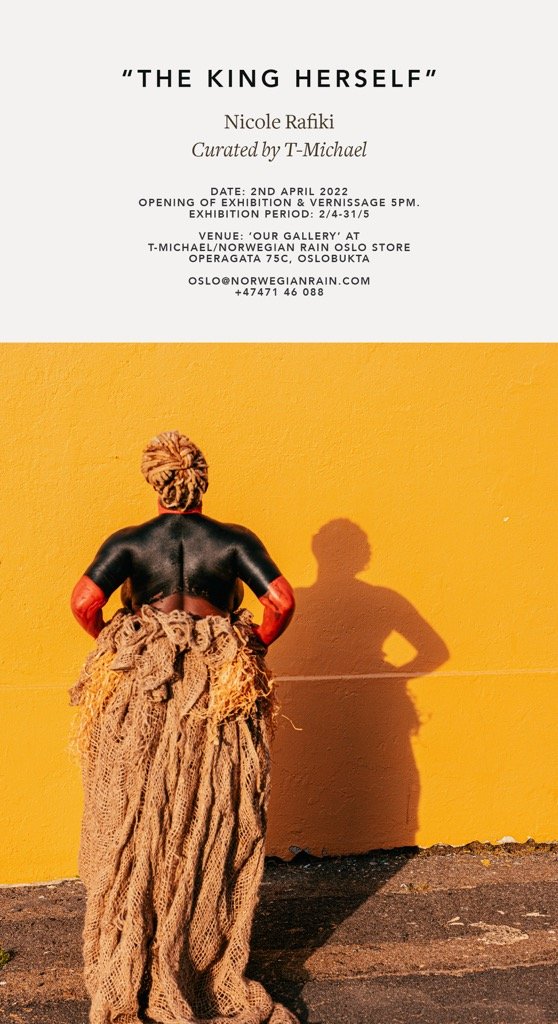

As a Kongolese artist who has long lived in the diaspora both on the African and the European continent, Rafiki is an artist of many localities, of movements both voluntary and involuntary. The point of describing her work thus does not lie in uncovering the reasons for such movements – sharing or not sharing them is up to the artist. What jumps to the eye of the viewer immediately however, is how the eyes and face are often covered in Rafiki’s work, by beads, hair, braided fabric or simply by pulling a T-shirt over one’s face or turning the back toward the lens.

This technique is also displayed in a couple of the images on show here in Oslo. Rafiki encountered Norway as a place where racial scripts of perception are already written. Deflecting the white gaze, turning it back on itself by preventing the soul of the photographed to be accessed or stolen through the eyes, as she puts it, is a self-protective measure against colonial mechanisms of ordering that are rooted in conventions of ethnographic photography and that expect the photographed to enact something that a western mind has already envisioned.

Choosing to engage in „auto-ethnography“ instead, Rafiki composes her own script of meanings, making her own kind of ritual or ceremony. One of which is letting go of the focus on the final printed picture. Rafiki’s photographic practice happens at multiple points in time so that all the steps that make a picture – from choosing a location to the choice of clothing and dress, objects and colors, to asking other artists to become subjects and collaborators – become part of the artistic practice equally until it is undecipherable when and where the photographs began and what their duration will be.

Rafiki’s auto-ethnographic strategy also lets it become clear that the impulse of immediately reading the exhibition title as genderqueer or identifying some kind of feminist ‚nakedness‘ in her images, can easily miss the mark of what is at play. Rafiki is not naked, she is clothed otherwise. Color can serve as a kind of dress and dousing herself in Tukula, a red pigment from ground redwood, or showing herself steeped in a dark bluish black hue, Rafiki conjures notions of cleansing oneself from colonial history (red) and personal rebirth (black), bringing these colors as close to her skin as possible.

Unlearning to fall back into a westernized standard of reading pictures, be they pop cultural products or presented in an arthistorical context, is a welcome side effect of Rafiki’s show. The larger artistic project she is building, and of which the images that form her hexaptych form an integral part, is a project that consists of and speaks to many polyphonic contexts and localities. At its heart is a conjuring of pre-colonial notions of fluidity that existed long before nation-states and colonial borders. Rafiki’s images speak to pre-colonial forms of aesthetics, pan-African kinds of knowledge productions, and modes of global interconnectedness that precede the white Western imperial project and its colonialist gaze.

Hers is a world of art rather than a hegemonic art world as we know it today with its white gates, classist keepers and neoliberal mechanisms of ``divide and conquer‘. In her artistic practice, Rafiki is not so much preoccupied by a gesture of refusal that placates how frequently Black bodies are asked to be molded into tokens of racial diversity. Those themes come to mind precisely because Rafiki is not lost in answering to them. As she words it, she is not in the business of performing Blackness: „I am not a public gesture“. Rather, she has dedicated herself to exploring artistic forms of healing vis-à-vis living in a post-colonial present with its multiple transatlantic pasts and intertwined continuities. The „auto-ethnography“ she practices with her artworks is also a practice of collectivity, a realised belief in the coevalness of places and spirits, futures, presents and pasts.

Noemi Y. Molitor, ph.d. Berlin based visual artist and researcher

—-------

If you´ve read this much, I know at least two things about you: you are curious and you care. Although my emotions were triggered by a personal tragedy, it also coincided with our collective ones, caused by ongoing environmental, racial and political violence globally, and to the ongoing pandemic. I can´t remember the last time I felt this vulnerable and exposed physically, mentally and emotionally. With the love and care of the many amazing people like you, who shared whatever they had — be it an open mind, a listening ear, a hug, heartfelt laughter or any other satisfying way of using their time around me, I have undergone a transition of energy from intense grief to reconciliation and internal peace. If time is money, then I´m ballin´, thanks to you all. You are too many to name here, but you should know that I see you. I thank my close and extended family members, whose resilience and joie de vivre through this rollercoaster journey is a never-ending source of inspiration. Mama and papa, what does a body do when the tongue is unable to speak the language of the heart? I hope the work gives you an idea. I am deeply thankful for the technical, creative and supportive participation of artists Asanda Hanabe, Patrick Bongoy, Kamyar Bineshtarigh, Billy Paul and Thomas Moll in this process. Thank you so much for the amazingly uplifting conversations that led to this exhibition, T. I appreciate you and the amazing community you and Alex have built around this beautifully fluid establishment. Asante sana for making room. We have arrived and we feel at home.

The best time to live is while we are alive. Let's do this, chale!

Rafiki, artist

Works:

102x132 cm

Beads, fishing gut and Digital Pigment Dye on canvas. Framed

1.We dream new dreams when the sky is blue

2-3. Sometimes hope hangs by a thread

4. Only a fool fights the sun

5.The king herself

6. We went back and fetched it

7. We have arrived

Prices on request

Nsambu

copper bracelets 3500 NOK

copper ankle bracelets 4000 NOK

copper bracelets were used as a trade currency in the 14. – 19th. Century in the Luba Empire. This collection was made exclusively by Lubumbashi (DRC) based artist and craftsman Billy Paul in collaboration with Rafiki

Madiba

Hand-made traditional textile 8000 NOK

woven mats with elaborate embroideries were originally made from the biodegradable Raffia palm leaves and natural colourants. Madiba is the foundation of the multilayered apparel worn by nobility and titled people in the Luba Empire and neighboring powers in the region, like the Kuba and Lunda kingdoms. Small pieces of Madiba were also used as trade currency before the introduction of european currency in 1887. This collection was made exclusively using recycled materials by Lubumbashi (DRC) based artist and craftsman Billy Paul in collaboration with Rafiki

Lukasa

memory board

Lukasa boards were used by the “men of memory”, masters of Luba history from the pre-colonial Mbudye society, to recount history. The tactile elements were accompanied by song and dance.

Not for sale.

Lupona:

Royal seat

Lupona is a metaforical royal stool of enthronement – a seat of leadership belonging to a king, emperor or chief. Lupona is never used for sitting, but rather serves as the embodiment and a reminder of the divine feminine source of power – the female aesthetics including elaborate hairstyles and scarification symbolise refinement and purity. This metaphor resonates with the Kemetic goddess Aset who held a similar position in Kemetic philosophy.

Not for sale.

Musamu:

Head rest

Used as a protective pillow for lay people or as a medium of communication with the spiritual world for a spiritual leader.

Not for sale.

Tubwa

Glass beads:

technique first developed in Kemet, then gradually exported to Europe (Venice and Murano) via the Byzantine empire. Venetian beads were used as a trade currency in the early days of the trans-atlantic slave trade and in the trans-Saharan slave trade. Glass beads spread out throughout the world through a triangulation of knowledge and craftsmanship.

Aesop´s tales

an Afro-European storyteller and freed-man who lived in Greece between 620 and 564 BCE. References from Aesop´s tales in latin:

“Washing the Ethiopian White” ( Whitewashing Black bodies) and

“The Quack frog” (Cura te ipsum: cure yourself first)